Where and why remote hydrogen monitoring is needed: real application scenarios

January 08, 2026According to Markets and Markets, global hydrogen demand is expected to grow steadily through 2030, driven by industrial decarbonization, mobility, and energy storage projects, with infrastructure investments accelerating after 2023. Given that hydrogen deployments scale, assets are increasingly distributed, semi-autonomous, and operated across multiple sites, often with limited on-site staffing. This exposes a structural gap: traditional hydrogen safety models rely on local detection and alarms: sensors trigger alerts that assume immediate human presence. In modern deployments, that assumption no longer holds. Many hydrogen assets operate remotely, across industrial zones, logistics corridors, or unmanned facilities.

Remote hydrogen monitoring addresses this gap by extending detection into an operational control layer. It provides real-time visibility, consistent alarm logic, historical traceability, and centralized oversight across sites. Let's take a look at where remote hydrogen monitoring is needed most and why it has become operationally unavoidable across the hydrogen value chain.

Why remote hydrogen monitoring becomes operationally mandatory

What was sufficient for isolated installations no longer works when assets are unmanned, geographically dispersed, and expected to operate continuously. Remote hydrogen monitoring emerges not as an optional enhancement, but as a necessary operational layer that connects safety, reliability, and economic performance. The following factors explain why centralized visibility and control are now fundamental to modern hydrogen deployments.

Safety and risk amplification

Hydrogen’s physical properties make it uniquely challenging to manage. It has a very low ignition energy, a wide flammability range, and diffuses rapidly through small openings. In enclosed or semi-enclosed environments, even a minor leak can quickly become hazardous if ventilation is compromised or ignition sources are present. Local alarms alone are often insufficient because they provide no operational context. An alert may indicate elevated hydrogen concentration, but it does not explain whether the cause is a short transient during regular operation, a ventilation failure, a valve malfunction, or an emerging equipment fault. Without signal correlation, operators are forced to choose between frequent shutdowns and unmanaged risk.

Operational and economic drivers

Beyond safety, hydrogen systems are capital-intensive and operationally sensitive. Compressors, electrolyzers, purifiers, and storage systems operate under high pressure and thermal stress. Slight deviations in operating conditions often precede failures by hours or days.

Remote monitoring enables:

- Early detection of abnormal trends before hard failures occur;

- Reduced unplanned downtime and maintenance costs;

- Fewer emergency site visits and callouts;

- Evidence-based maintenance planning instead of reactive repairs.

From an economic perspective, this is critical. Industry analyses consistently identify O&M costs and downtime as significant barriers to hydrogen project bankability. Investors and insurers increasingly expect continuous monitoring and documented control mechanisms, not just safety certifications at commissioning.

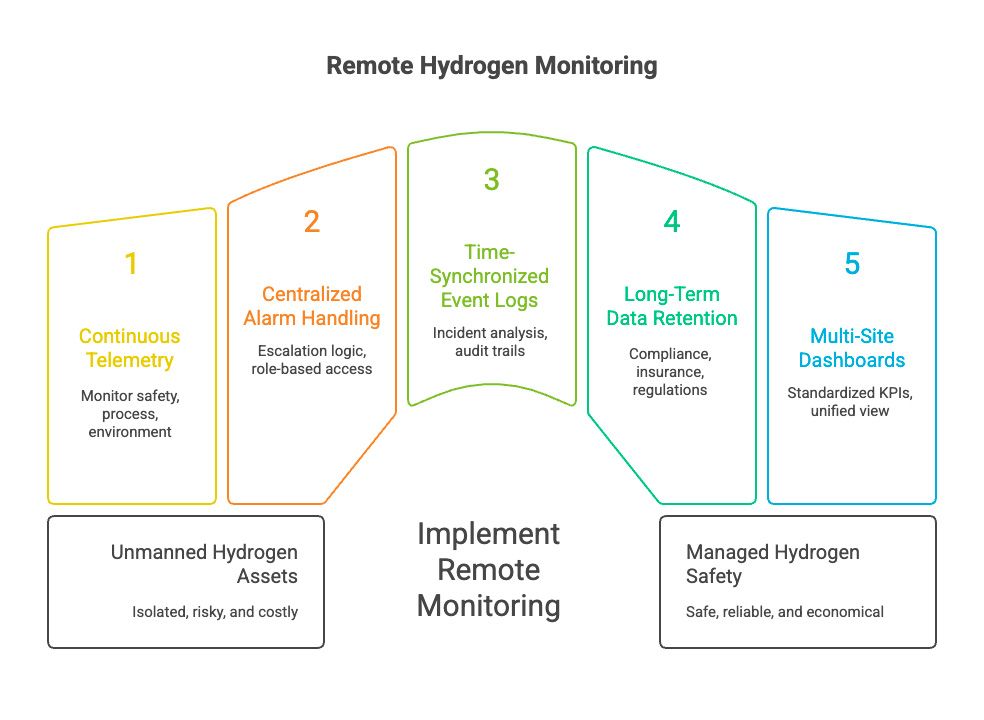

What “remote monitoring” actually means in practice

Remote hydrogen monitoring is not simply “viewing sensor data in the cloud.” In mature deployments, it includes:

- Continuous telemetry from safety, process, and environmental sensors;

- Centralized alarm handling with escalation logic and role-based access;

- Time-synchronized event logs for incident analysis;

- Long-term data retention for audits, insurance, and regulators;

- Multi-site dashboards with standardized KPIs.

In practice, remote monitoring turns hydrogen safety into a managed system rather than a collection of isolated devices.

Production sites and hydrogen hubs (electrolyzers, SMR/ATR, on-site generation)

Hydrogen production facilities are among the most complex environments to monitor. Modern sites typically include containerized electrolyzers, rectifiers, cooling systems, compressors, dryers, and buffer storage, all of which interact dynamically based on power availability, demand, and ambient conditions. Many of these facilities are lightly staffed or fully unmanned for long periods. When faults occur outside working hours, local alarms provide little operational value. Remote monitoring allows centralized teams to detect issues, assess severity, and determine whether immediate intervention is required or if maintenance can be scheduled safely.

Crucially, production-site monitoring must go beyond hydrogen concentration alone. Safety signals need to be correlated with process and equipment health data, such as pressure trends, temperature gradients, compressor duty cycles, power quality, and ventilation status. This correlation enables operators to distinguish between benign transients and escalating faults. As hydrogen hubs expand across regions, standardization becomes essential. Remote monitoring supports consistent alarm thresholds, shared KPIs, and comparative analysis across sites. Regulators and insurers increasingly expect operators to demonstrate systematic risk management across their entire asset portfolio, not just at the site level.

Storage, transport, and distribution infrastructure

Hydrogen storage and logistics introduce a distinct risk profile. Incidents are more likely to occur during transitions – filling, unloading, and pressure equalization – rather than during steady-state storage.

Remote hydrogen monitoring is particularly critical in:

- Bulk compressed or liquid hydrogen storage facilities;

- Tube trailer loading and unloading areas;

- Industrial depots and staging yards;

- Ports and hydrogen corridors with shared infrastructure.

In these environments, operations are often short-lived but high-risk. A loading operation may last only minutes, yet any leak during that window can have serious consequences. Remote monitoring provides a complete, time-stamped record of sensor readings, valve states, alarms, and operator actions. Distribution sites also tend to involve multiple stakeholders. Storage operators, logistics providers, port authorities, and end users may all share responsibility. Remote monitoring provides a neutral, auditable source of truth to support incident investigation, regulatory reporting, and liability clarification. As hydrogen logistics scale, digital traceability becomes as important as physical containment.

Refuelling stations and fleet depots (HRS, bus & truck operations)

Hydrogen refuelling stations (HRS) are among the most monitoring-intensive hydrogen applications. They combine very high pressures with frequent human interaction and demanding uptime requirements, particularly in fleet operations. From an operational standpoint, many HRS issues are not catastrophic failures but progressive degradation: compressors losing efficiency, valves wearing unevenly, dispensers drifting outside optimal operating ranges. Left undetected, these issues eventually trigger safety shutdowns that take stations offline.

Remote monitoring enables operators to:

- Detect early signs of degradation before safety trips occur;

- Coordinate maintenance across multiple stations from a central team;

- Reduce mean time to repair by arriving with proper diagnostics and parts;

- Maintain consistent safety standards across a growing station network.

Industrial and energy end-use applications

In industrial environments, hydrogen is often mission-critical rather than experimental. Refineries, chemical plants, steel production facilities, and emerging hydrogen-based power systems depend on continuous hydrogen availability and predictable system behavior. Here, the primary risk is not only safety but production impact. A hydrogen interruption can halt entire process chains, leading to cascading losses. Remote monitoring allows operators to correlate safety data with process stability, purity, and supply continuity, enabling faster diagnosis and better decision-making. Many industrial hydrogen deployments are integrated into brownfield sites with legacy SCADA systems, mixed protocols, and uneven security postures. Remote monitoring platforms must normalize data from diverse sources while maintaining strict access control and auditability. As hydrogen expands into backup power systems, fuel cells, and pilot blending projects, remote monitoring also plays a validation role, proving long-term reliability to regulators, insurers, and investors.

You may be interested in: Hydrogen detection market: size, trends, forecasts, and key figures.

How Kaa supports remote hydrogen monitoring at scale

Kaa provides a centralized operational platform designed for remote hydrogen monitoring across distributed assets. It aggregates data from hydrogen sensors, controllers, PLCs, and gateways into a single monitoring layer that supports both safety oversight and operational control.

With Kaa hydrogen remote monitoring solution, operators can:

- Collect continuous telemetry from safety, process, and environmental signals;

- Configure real-time alerts with escalation rules and role-based access;

- Maintain long-term, tamper-resistant event histories for audits and investigations;

- Monitor multiple hydrogen sites through standardized dashboards and KPIs;

- Integrate hydrogen monitoring data with CMMS, dispatch, and incident-management systems via APIs.

This approach has been applied in real industrial monitoring deployments, including hydrogen-related use cases where assets are geographically dispersed and managed by lean teams. A detailed example is available on the Kaa website, illustrating how centralized monitoring improves response time, visibility, and compliance across multi-site environments.

Conclusion

Across production sites, storage and logistics infrastructure, refuelling stations, and industrial end use, the same pattern emerges. Hydrogen systems are distributed, high-consequence, and operationally complex. Local detection alone does not provide the visibility or control required at scale. Remote hydrogen monitoring transforms safety devices into a coordinated operational system. It enables faster response, better maintenance decisions, and defensible compliance in an environment where failures are costly and scrutiny continues to increase. As hydrogen infrastructure moves beyond pilots into core energy and industrial systems, remote monitoring is no longer optional – it is a foundational requirement for safe, scalable hydrogen operations.