The real cost of closed clouds in energy monitoring

November 26, 2025Most energy operators know the feeling: you open a monitoring portal to check a fault or confirm yesterday’s production, and the dashboard doesn’t load. The vendor’s cloud is down, and with it goes your ability to analyze or respond. The outage might be temporary, but it reveals a more profound weakness: the extent to which operators surrender control when monitoring depends entirely on a vendor-hosted cloud.

For years, low-cost dataloggers with bundled portals helped solar and industrial systems scale quickly. They simplified installations and offered enough visibility for basic oversight. But today, monitoring data underpins compliance reporting, grid interactions, operational forecasting, and financial decisions. This shift has turned closed, opaque cloud ecosystems from a convenience into a structural risk.

A closed cloud dictates how your devices communicate, where your data resides, and whether you’re free to switch platforms. Read on to understand why this dependency quietly becomes more expensive over time.

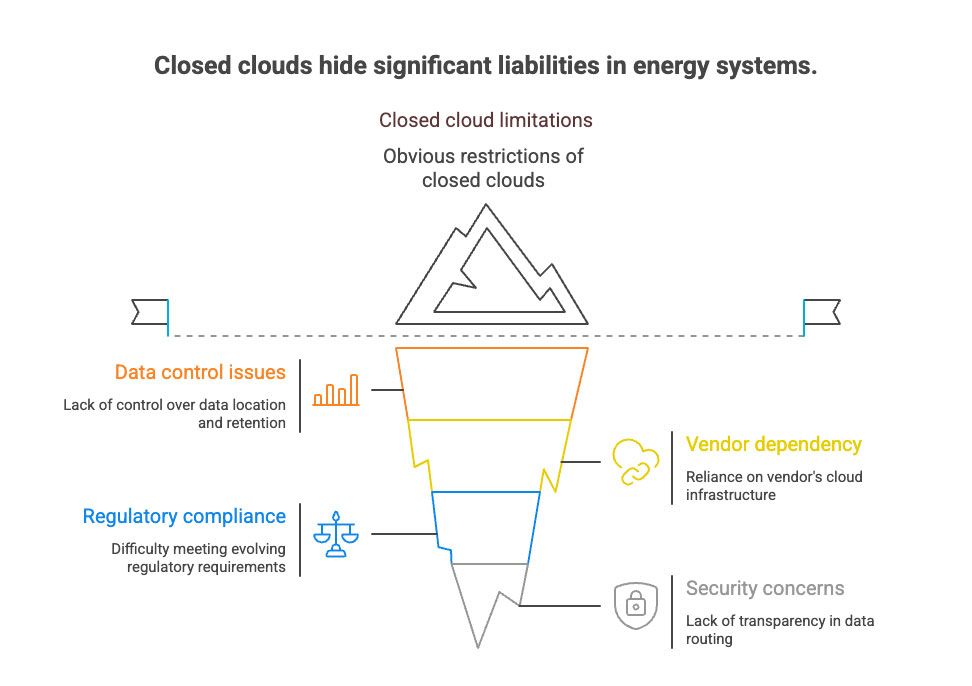

Why closed clouds became a hidden liability in modern energy systems

Energy monitoring used to be a secondary layer in project design, helpful for performance checks, but not essential for day-to-day operations. That era is over. Today, monitoring data supports warranty claims, informs financial models, feeds ESG reporting, shapes grid-interaction strategies, and influences eligibility for incentives. As the role of telemetry expanded, the limitations of closed, vendor-controlled clouds became far more consequential.

In a closed-cloud architecture, telemetry travels through a single, proprietary path: a device talks only to the vendor’s portal, APIs are restricted or monetized, and hosting locations are often undisclosed. Operators cannot choose where data lives, how long it is retained, or how it integrates with other systems. If the cloud slows, changes policy, or experiences an outage, the operator has no fallback mechanism and no control over remediation. That dependency becomes especially risky when monitoring feeds financial models or supports regulatory reporting.

This challenge is growing more visible in the U.S., where regulatory and market pressures are rapidly evolving. The Inflation Reduction Act introduced FEOC (Foreign Entity of Concern) restrictions, making the provenance of both hardware and cloud infrastructure a serious consideration for project eligibility. Energy companies undergoing cybersecurity reviews increasingly need clarity on data routing, storage locations, and vendor practices – information that many closed platforms simply do not disclose.

This is one reason why open, locally buffered systems like the Kaa Energy Data Logger are gaining traction among operators seeking transparent data flow and audit-ready architectures. So what are the real business, security, and compliance costs of relying on closed clouds, and who ultimately pays them?

The hidden costs everyone ignores (until something breaks)

Closed-cloud monitoring often appears cost-efficient at first: inexpensive hardware, a ready-made portal, and quick deployment. But once systems enter real-world operation, deeper costs emerge – financial, operational, and regulatory. These costs don’t spike immediately; they accumulate quietly until they dictate how the entire monitoring stack can (or cannot) evolve.

Vendor lock-in and lifetime cost inflation

Closed-cloud vendors control the full path from device to database. That control becomes restrictive as fleets grow. Telemetry cannot be redirected to another system, exports are limited or incomplete, and API access, if available, frequently becomes a paid tier over time. What began as a simple portal dependency turns into a structural cost obligation.

Large operators feel this most. A company with hundreds of sites often discovers that the only way to consolidate monitoring is to replace the very hardware that forced them into the vendor’s cloud. Devices locked to a single ecosystem make platform migration expensive, slow, and operationally disruptive, far more so than the original installation.

Compliance exposure (GDPR, NIS2, FEOC)

As regulators tighten cybersecurity and data-sovereignty requirements, closed clouds introduce compliance blind spots. Operators may not know where data is stored, which subcontractors access it, or whether the vendor aligns with the security controls required in audits. In the U.S., FEOC rules under the Inflation Reduction Act have raised the importance of understanding the origin of both hardware and software components. Projects involving infrastructure tied to Foreign Entities of Concern risk losing incentives. Meanwhile, frameworks such as Europe’s NIS2, while not directly binding in the U.S., shape industry expectations around traceability and secure software supply chains. Closed platforms rarely provide the documentation needed to demonstrate this level of transparency.

Operational downtime and data gaps

Closed-cloud architectures rely on uninterrupted connectivity to the vendor’s servers. When the cloud experiences an outage or a latency spike, monitoring stalls. Without local buffering or edge storage, telemetry may never be recovered. These gaps complicate warranty negotiations, distort performance models, and extend troubleshooting time. End customers usually hold the integrator responsible, even when the root cause lies entirely with the vendor’s infrastructure.

Security blind spots

Vendors using proprietary stacks often reveal little about firmware provenance, patch schedules, or internal routing practices. Many budget dataloggers ship with outdated firmware that carries unpatched vulnerabilities – issues operators may not even be aware of. Without access to reliable APIs, logs, or integration hooks, teams cannot apply zero-trust principles, connect SIEM tools, or validate that data paths comply with internal security policies.

You may be interested in: Why energy data should stay local?

The multiplier effect: how closed clouds limit portfolio growth and scalability

Closed-cloud limitations don’t stay small. As portfolios expand, the constraints compound, turning manageable inefficiencies into structural bottlenecks. This is especially visible in the U.S. market, where operators rarely oversee a single asset type. A typical portfolio blends solar, battery storage, EV charging, HVAC systems, backup generation, and grid-interactive controllers, all of which must exchange data reliably to keep operations efficient. Closed platforms fracture that picture. Each vendor dictates its own portal, data model, and access rules. As diversity increases, operators end up with parallel monitoring environments that cannot communicate with each other. Even routine tasks, such as comparing site performance, correlating solar output with HVAC load, or analyzing BESS charge cycles, require toggling between unrelated dashboards. For teams managing dozens or hundreds of facilities, the administrative overhead grows faster than the portfolio itself.

A major contributor is the lack of support for open industrial and IoT standards. IoT Protocols such as Modbus, MQTT, REST, OPC UA, and IEC 61850 are the foundation of modern energy interoperability. Yet many cloud-locked devices rely on proprietary communication protocols that cannot be directly integrated into other systems. Without these widely adopted standards, equipment remains isolated, and the operator loses the ability to unify telemetry or orchestrate cross-asset automation. This fragmentation also incurs operational costs. Each closed ecosystem requires its own training, troubleshooting, and certification process. Onboarding new technicians becomes slower, and knowledge gaps appear whenever staffing changes. For EPCs and long-term service partners, this increases the cost of delivering consistent support across a distributed asset base.

Financially, the effect is multiplicative. Every new site added to a closed ecosystem reinforces the dependency, introducing additional licensing terms, portal constraints, and integration limitations. At a certain point, the portfolio’s growth is constrained not by hardware capabilities but by the monitoring architecture itself. Scalability depends on the opposite model: an open, vendor-agnostic architecture that treats all devices as part of a single operational layer. When equipment can communicate through standard protocols and feed into a shared data pipeline, portfolios grow without amplifying administrative or technical overhead.

Open monitoring architecture as the answer: what it actually looks like

The alternative to closed-cloud monitoring is a structured, open architecture that unifies diverse energy assets under a single, transparent data layer. An open monitoring architecture starts with device-agnostic ingestion: any inverter, battery system, EV charger, or industrial controller can send telemetry through interoperable protocols rather than a vendor-defined gateway. APIs are transparent, data schemas are documented, and operators control where the system is hosted: on-premises, in a private cloud, or in a hybrid configuration that satisfies regulatory requirements.

Most importantly, open doesn’t mean “DIY chaos.” A mature architecture provides all the elements operators expect from modern monitoring platforms:

- Interoperable protocols, so that equipment from different vendors can speak the same language.

- Digital twins represent each asset with real-time state, historical data, and structured metadata.

- Real-time telemetry processing for alarms, analytics, and predictive maintenance.

- Local buffering with optional cloud sync, ensuring no data gaps during outages.

- Flexible deployment models for regulated sectors that require domestic data storage or full control of their cybersecurity posture.

Consider a utility-scale operator managing solar, BESS, and high-load industrial HVAC across hundreds of distributed sites. With closed clouds, they juggle dozens of portals and inconsistent export formats. But with an open architecture, all devices report to a unified ingestion layer, data is normalized automatically, and dashboards reflect the entire portfolio in real time. If business needs evolve, new devices or analytics engines can be added without waiting for a vendor’s development roadmap.

Kaa enables this by offering an API-first device management and data pipeline layer that doesn’t force operators into any predefined cloud. Control stays with the integrator or asset owner.

TCO comparison: closed cloud vs. open architecture

Even when closed-cloud hardware seems inexpensive upfront, long-term ownership tells a different story. Because vendors control the entire data path, costs compound through subscription fees, API restrictions, and forced migrations. Open architectures, by contrast, keep infrastructure transparent and operator-driven, which stabilizes costs over time.

Below is a refined comparison based on common cost categories across 3–7 years of operation:

| Cost Category | Closed Cloud Monitoring | Open Monitoring Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Cost | Low initial price, but tied exclusively to the vendor’s cloud; hardware becomes unusable if switching platforms. | Slightly higher upfront costs, but protocol-based communication keeps hardware compatible across systems. |

| Subscriptions | Mandatory recurring fees; charges typically scale with asset count. | No required portal fees; hosting model is fully operator-controlled. |

| API Access | Often limited or paywalled; export formats inconsistent. | Transparent, full-featured APIs designed for integration and analytics. |

| Downtime Impact | Cloud interruptions cause telemetry loss with no local fallback. | Local buffering and edge storage preserve data during outages. |

| Compliance Exposure | Data residency and security posture often unclear; difficult to document controls during audits or incentive reviews. | Operators choose storage region and can align hosting with regulatory requirements. |

| Migration Cost | High – typically requires hardware replacement due to cloud lock-in. | Low – open protocols enable phased migration without replacing devices. |

| Long-Term TCO | Increases sharply with portfolio size and subscription layers. | Stabilizes after initial setup; predictable and scalable. |

In practice, operators find that openness pays for itself by avoiding recurring licensing and device replacement cycles. Once the monitoring environment is no longer tied to vendor-specific infrastructure, both operational and financial planning become more predictable.

How to decide: when closed cloud is acceptable – and when it becomes a strategic risk

Closed-cloud monitoring has its place. For small residential systems, where data needs are simple and long-term ownership isn’t a priority, a vendor-managed portal can be perfectly adequate. Homeowners typically want to see daily production, receive alerts, and avoid managing infrastructure. In those cases, simplicity outweighs flexibility. The calculus changes entirely for commercial, industrial, and utility-scale operators. Once an organization begins managing multiple sites or relies on telemetry for financial accuracy, equipment warranties, or operational coordination, the limitations of closed ecosystems quickly become liabilities. Historical data must remain accessible, integrations must scale, and monitoring must continue even when the network doesn’t. Closed clouds rarely offer that level of assurance.

Compliance adds another layer of consideration. Regulatory frameworks and incentive programs increasingly require clarity around data routing, storage location, and software provenance. If a vendor cannot provide the level of transparency required by auditors, operators risk delays, additional costs, or eligibility issues. The details matter more as asset counts grow and monitoring becomes intertwined with reporting obligations.

A practical way to evaluate the decision is to consider how monitoring failure would affect operations. If losing access to data, even temporarily, would disrupt revenue calculations, warranty claims, building operations, or ESG reporting, relying on a vendor-controlled cloud shifts too much risk outside the operator’s control. Likewise, if hardware tied to a proprietary cloud would need to be replaced during a future platform change, the long-term cost becomes difficult to justify. Choosing an open architecture is not about favoring one technology model over another. It is about ensuring that energy systems remain flexible, transparent, and reliable as portfolios expand and regulatory expectations evolve.

Conclusion

Closed-cloud monitoring gained popularity because it offered simplicity and low initial cost, but those advantages fade as energy systems scale and regulations tighten. The risks that once seemed theoretical (constrained integrations, unclear data residency, limited visibility during outages) now carry direct operational and financial consequences. As energy infrastructure becomes more distributed and digitally integrated, losing control over the monitoring layer is no longer sustainable.

Open architectures shift that balance back toward the operator. They allow organizations to decide where data is stored, how systems integrate, and how the monitoring stack evolves over time. This flexibility isn’t just a technical preference; it’s a safeguard for long-term resilience, compliance, and operational independence.

If you’re considering a transition toward a more open, future-proof monitoring model, including Kaa-powered options, our team can help evaluate the best approach for your portfolio.