Risks identified when using Chinese solar inverters and batteries

January 02, 2026Utility-scale solar and behind-the-meter energy systems increasingly depend on digitally controlled power electronics, primarily solar inverters and battery energy storage systems (BESS). These devices now function as active control nodes, influencing grid stability, power quality, and real-time operational behavior. As connectivity expands, so does risk. Undocumented functionality, opaque firmware behavior, unmanaged remote access, and reliance on vendor-controlled cloud platforms can undermine operator visibility and control. In this context, concerns around Chinese-manufactured inverters and batteries are less about country of origin and more about architecture, transparency, and system-level trust. For energy operators and EPCs, the critical question is no longer who built the hardware, but how much control remains after deployment.

Let's examine the practical risks embedded in modern inverter and BESS architectures and check how they can be mitigated at the system level.

Undocumented communication paths in modern inverters and BESS

Recent findings have drawn attention to the presence of undocumented communication components in certain Chinese-manufactured solar inverters and battery energy storage systems (BESS) deployed across global power networks. According to Reuters, these components, including cellular radios and similar communication modules, are not described in publicly available specifications, technical documentation, or user manuals provided to operators and integrators. The issue is not connectivity itself. Inverters and batteries routinely exchange data for telemetry, firmware updates, performance optimization, and remote support. The risk arises when communication capabilities exist outside documented and operator-controlled channels, creating uncertainty around how devices connect, where data flows, and under what conditions remote commands may be accepted.

Investigations point to several recurring risk factors: undocumented communication modules not declared in technical specifications, unknown outbound connectivity paths, including cellular-based links, limited ability for operators to audit or disable these channels using standard network controls, and reduced visibility into how remote commands are issued and executed. Such hidden communication paths undermine conventional assumptions in cybersecurity. Firewalls, VPNs, and network segmentation are effective only when all interfaces are known and governed. When devices contain non-transparent communication capabilities, these protections may be bypassed without triggering traditional security alerts. At scale, particularly in high-penetration solar or storage environments, this loss of visibility and control represents not only a cybersecurity concern but a direct risk to grid stability and operational reliability.

Firmware and network-level exposure in solar inverters

Risks associated with modern solar inverters and battery systems extend beyond undocumented hardware components. Independent security analysis and incident reporting have shown that firmware design and network exposure introduce systemic vulnerabilities affecting a wide range of solar equipment, including products from globally recognized vendors. Assessments of inverter software stacks have identified weaknesses in authentication mechanisms, remote management interfaces, and update workflows. In some scenarios, these flaws could enable unauthorized access, manipulation of operating modes, or remote device disabling. When such weaknesses exist across large inverter fleets, particularly in utility-scale or highly distributed environments, their impact can propagate quickly and affect grid operations.

Reporting by Cybersecurity Dive has highlighted that common inverter architectures may be vulnerable to remote sabotage when exposed through poorly secured network interfaces or cloud-connected management layers, even in the absence of malicious hardware. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that software behavior and network architecture are as critical as hardware integrity. Even fully documented devices can pose material risk if firmware remains opaque, remote access paths are insufficiently governed, or operational visibility is limited. Inverter cybersecurity, therefore, must be evaluated as a system-level property rather than a device-level feature.

Why these risks matter

The risks associated with modern solar inverters and battery systems are not theoretical or confined to isolated cybersecurity incidents. As solar penetration increases and power electronics assume more grid-facing responsibilities, weaknesses at the inverter and control layers translate directly into operational, systemic, and strategic consequences.

Impact on grid stability and operational control

Solar inverters no longer serve solely as electrical converters. Modern “smart” inverters actively participate in grid operations by regulating frequency and voltage, managing reactive power, supporting ride-through during disturbances, and balancing loads across interconnected systems. These capabilities are essential in grids with high shares of renewable generation, where inertia is lower, and system dynamics are more sensitive.

When control or telemetry pathways are compromised, whether through undocumented communication channels, vulnerable firmware, or opaque remote management, operators risk losing accurate visibility into system behavior. In the worst case, unauthorized control actions could force inverters into unstable operating modes, trigger coordinated shutdowns, or distort grid-balancing signals. When replicated across large fleets, even localized disruptions can cascade into broader service interruptions.

National security and strategic infrastructure risk

Beyond operational impacts, inverter and battery vulnerabilities raise broader national security concerns. Power electronics are increasingly treated as critical digital infrastructure, and large-scale dependence on equipment with limited transparency introduces strategic exposure. Hidden access paths or poorly governed remote-control mechanisms could, in theory, be exploited during periods of geopolitical tension to disrupt energy supply without direct physical intervention.

While debate continues over whether such risks stem from intentional design choices or insufficient oversight, the distinction is largely irrelevant from a risk-management perspective. What matters is whether operators can independently verify, monitor, and constrain the behavior of essential energy assets. In an environment where energy resilience is closely tied to economic and political stability, loss of control carries consequences well beyond the technical domain.

Differentiating risk from hype

It is important to avoid oversimplification. Not every Chinese-manufactured device contains hostile backdoors, and many cybersecurity weaknesses are common across industrial electronics regardless of origin. Undisclosed hardware may result from documentation gaps rather than malicious intent, and exploitation typically requires technical expertise and favorable conditions. That said, risk management does not depend on proving intent. The combination of limited transparency, opaque firmware behavior, and documented exposure of control interfaces creates a credible risk surface that must be addressed proactively, particularly in systems that form part of critical energy infrastructure.

Regulatory and industry responses

As digital power electronics become deeply embedded in energy systems, regulators and market participants are reassessing how solar inverters and battery technologies are evaluated, procured, and governed. Attention is shifting from price and efficiency alone toward cybersecurity posture, transparency, and supply-chain resilience.

Regulatory responses in the U.S. and Europe

In the United States, federal agencies have increased scrutiny of inverter and battery technologies used in grid-connected environments. Energy authorities are assessing risks related to undocumented functionality, remote access paths, and opaque firmware behavior, while encouraging stronger documentation requirements and more transparent disclosure of communication interfaces. Legislative discussions have also explored measures to limit or condition procurement of specific foreign-manufactured energy components in sensitive or publicly funded projects.

In parallel, European policymakers are evaluating whether photovoltaic inverters should be classified as important products with digital elements under emerging cyber-resilience frameworks. Such classification would impose stricter requirements around secure-by-design principles, vulnerability management, and lifecycle transparency, aligning solar infrastructure with standards applied to other critical digital systems.

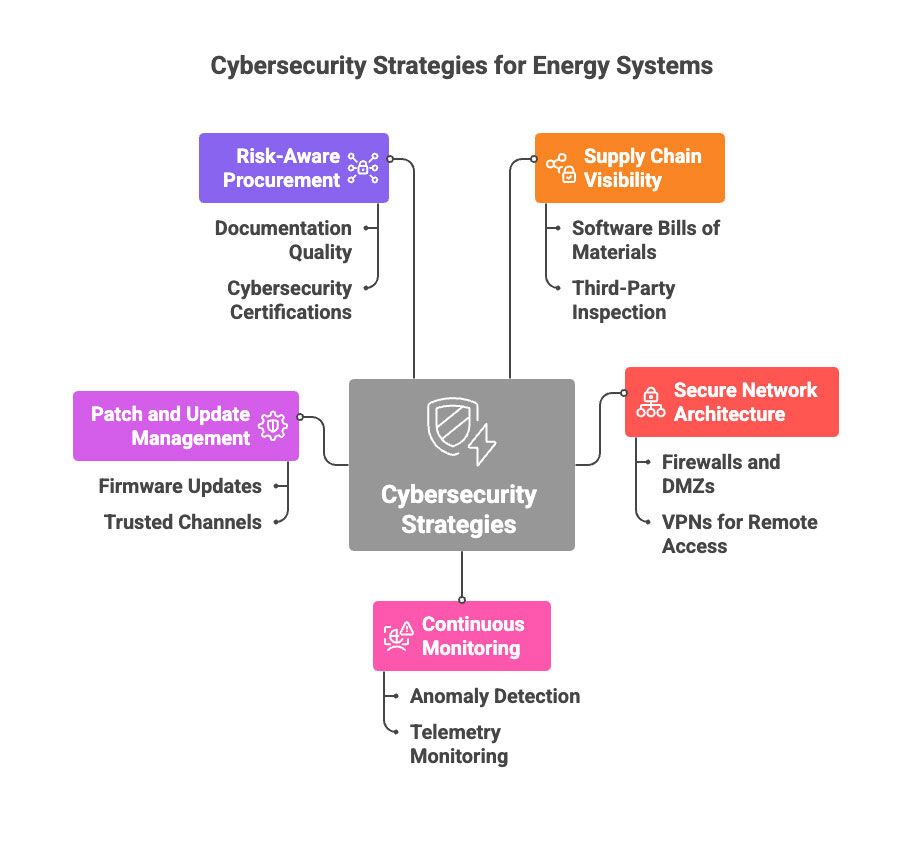

Industry-led mitigation efforts

Alongside regulatory activity, utilities, EPCs, and large asset owners are taking independent steps to reduce exposure. These include diversifying inverter and BESS suppliers, introducing cybersecurity and architectural reviews into procurement processes, requiring third-party security assessments, and placing greater emphasis on system architectures that preserve local control and independent monitoring. Collectively, these actions reflect a growing recognition that inverter risk management extends beyond device selection and into long-term system design.

How KaaIoT Universal Energy Controller reduces inverter and battery risk

The risks outlined above share a common root cause: lack of independent visibility and control at the device level. The KaaIoT Universal Energy Controller is designed to address this gap. Rather than relying on inverter-native cloud platforms or proprietary OEM control channels, KaaIoT introduces an independent, hardware-agnostic control layer deployed at the edge. Inverters and battery systems communicate with a local controller instead of directly with external vendor clouds. This architecture allows operators to explicitly define, monitor, and audit outbound connections, reducing exposure to undocumented communication paths.

By decoupling control logic from inverter firmware, the Universal Energy Controller minimizes reliance on closed OEM software stacks. Telemetry is validated at the edge, correlated with meter and grid signals, and monitored for anomalies that may indicate malfunction or unauthorized behavior. The platform also provides fleet-level visibility across mixed-vendor environments, enabling operators to manage risk consistently across diverse portfolios. This approach does not eliminate all device-level risk. Still, it materially reduces its systemic impact, supporting architectures that prioritize transparency, local control, and operational resilience without requiring immediate hardware replacement.

Conclusion

Solar inverters and battery systems are indispensable to modern energy infrastructure, but their increasing complexity and connectivity introduce new classes of risk. Undocumented communication paths, opaque firmware behavior, and vulnerable control architectures demonstrate that cybersecurity and hardware integrity must be considered together and at the system level. Addressing these challenges requires more than device certification or vendor trust. It demands architectures that preserve operator control, enforce transparency, and reduce dependence on opaque external platforms.