How to secure solar data loggers from cyber threats and unauthorized access

January 05, 2026Solar data loggers have become a central point of trust in modern PV systems. They collect inverter and meter data, validate signals, and deliver the telemetry used for billing, grid compliance, and performance analysis. Because they sit between field devices and cloud platforms, they also represent one of the most attractive entry points for attackers. Most compromises stem from predictable weaknesses: open ports, outdated firmware, unencrypted Modbus traffic, shared installer accounts, and hard-coded cloud endpoints. A breached logger can do more than distort production data; it can expose customer network resources, allow unauthorized inverter commands, or disrupt export-limit controls required by utilities.

Provided that distributed energy grows, securing telemetry is getting as important as securing the electrical infrastructure itself. Let’s break down the current threat landscape, the security requirements for modern data loggers, and the measures that EPCs, O&M teams, and asset owners should use to protect their installations from cyber risks and unauthorized access.

Threat landscape for solar data loggers

Most attacks on solar data loggers follow predictable vectors. Weak or default credentials remain the easiest entry point, especially in fleets where installers reuse passwords. Open ports (commonly 80, 502, 1883, and sometimes even 8883) expose devices directly to the internet. Many inverters and loggers still transmit Modbus RTU/TCP data in plain text, making interception trivial. Insecure OTA update mechanisms allow tampered firmware to be installed without proper signature checks. Hard-coded cloud endpoints create additional risk when traffic cannot be redirected or audited. Vendor-locked gateways with outdated or poorly maintained firmware add another layer of exposure across mixed-vendor sites.

A successful breach can have immediate operational and financial impact. Attackers may trigger unauthorized inverter shutdowns or alter performance data, leading to billing errors and PPA disputes. Manipulating export limits or grid-compliance parameters can cause regulatory violations. Once inside the logger, attackers can pivot into the wider LAN, accessing routers, cameras, or NAS devices. Even passive data theft is damaging, as consumption profiles often reveal occupancy patterns and business activity.

Security requirements for modern solar loggers

Modern solar data loggers must meet a higher security baseline than traditional industrial gateways. They operate in distributed environments, communicate with multiple inverter vendors, and often connect directly to the public internet. Because of this, weaknesses at the hardware, firmware, or network layers can compromise the entire monitoring stack. The table below summarizes the minimum technical requirements a logger should meet to ensure safe operation, reliable telemetry, and protection against unauthorized access.

Security requirements overview

| Layer | Requirement | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Secure boot + firmware signing | Ensures the device runs only verified, untampered firmware. |

| FEOC-compliant chipset sourcing | Prevents reliance on unverified or insecure SoC components. | |

| Physical tamper resistance | Protects against local access attempts and hardware manipulation. | |

| Software & firmware | Encrypted storage | Keys, Wi-Fi credentials, and tokens must be stored securely. |

| Secure device identity (X.509) | Each logger must have a unique, cryptographically verifiable identity. | |

| Regular OTA security patching | Ensures timely delivery of vulnerability fixes and firmware updates. | |

| Network | TLS 1.2/1.3 for MQTT/HTTPS | Encrypts telemetry and command channels end-to-end. |

| No plaintext Modbus traffic | Field protocols must be wrapped or isolated via a secure gateway. | |

| Role-based firewall rules | No inbound ports; the device communicates only outbound under strict rules. |

Best practices for securing solar telemetry

Securing telemetry is the most effective way to protect a solar installation from operational disruption and data manipulation. Because loggers sit between inverters, meters, and cloud platforms, any weakness in authentication, encryption, or network configuration becomes a direct entry point for attackers. The following practices outline the minimum safeguards required to maintain data integrity, prevent unauthorized commands, and ensure that monitoring systems remain trustworthy across residential, commercial, and utility-scale deployments.

Strong authentication & credential hygiene

Solar loggers must use unique device credentials and avoid any form of shared or default passwords. Rotating tokens or per-site access keys reduces the risk of long-term credential exposure. Cloud dashboards should enforce MFA, especially for installer and O&M accounts with write permissions. EPC teams should never reuse a single cloud account across multiple sites – this remains one of the most common sources of large-scale compromise.

- Encrypted communication end-to-end. Telemetry must be encrypted from the field device to the cloud. MQTT over TLS (port 8883) and HTTPS with certificate pinning prevent interception and tampering. For on-prem systems, a VPN tunnel ensures that data remains within a controlled network perimeter and prevents unauthorized device polling.

- Close all unused ports & services. Loggers should expose no inbound services. Telnet and HTTP must be disabled entirely, and Modbus should never be accessible over a public IP. Firewall policies should enforce outbound-only behavior, limiting communication strictly to approved cloud endpoints.

- Secure Modbus traffic. Since Modbus provides no built-in security, it should be wrapped through a secure gateway that converts RTU/TCP signals into MQTT/TLS. The inverter LAN must be isolated from the building network to prevent cross-device exposure. Only the minimum required registers should be accessible to reduce risk from unauthorized write commands.

- Hardening the local network. Solar equipment should operate on a dedicated VLAN to restrict lateral movement if a device is compromised. Access controls must ensure that loggers cannot reach unrelated LAN resources. For Wi-Fi devices, WPA3 is mandatory, and WPS should be disabled to eliminate brute-force entry points.

- Continuous monitoring & audit logs. Adequate security requires real-time visibility. Loggers and gateways should detect anomaly patterns, such as unexpected write commands, irregular spikes in telemetry, or configuration changes. Edge-level buffering helps identify replay attacks by validating timestamps and sequence integrity. Audit logs enable O&M teams to trace events, correlate alerts, and respond quickly.

The role of edge gateways in logger security

Edge gateways have become a critical security layer in modern PV systems. They sit between field devices and external networks, isolating insecure protocols, enforcing encryption, and validating every data point before it leaves the site. Instead of allowing inverters or meters to communicate directly with the internet, a gateway creates a controlled boundary where traffic can be authenticated, filtered, and monitored. This architecture significantly reduces the attack surface and standardizes security across mixed-vendor environments.

Why dedicated gateways reduce risk

Dedicated gateways protect solar systems by separating unsecured field protocols, such as Modbus, from the public internet. They provide TLS termination, enforce firewall rules, and maintain secure device identities, ensuring that only authenticated traffic leaves the site. A gateway also enables secure OTA updates and key rotation – capabilities that many inverters and low-cost loggers lack. By centralizing these controls, the gateway becomes the anchor of site-level cybersecurity.

Example architecture: secure solar telemetry flow

A secure telemetry architecture isolates each layer of the PV system while ensuring that data is validated and encrypted before leaving the site. The flow below reflects a modern, high-security design used in commercial and utility-scale deployments:

1. Panels → inverter (Modbus RTU/TCP). The inverter exposes electrical parameters, such as voltage, current, power, and grid status, via Modbus. This protocol is reliable and straightforward, but completely unsecured: no encryption, no authentication, and full read/write access if unprotected. Because of this, Modbus must never be exposed outside the local field network.

2. Inverter → secure edge gateway / energy logger. The gateway connects to the inverter over Modbus but acts as a security boundary. It performs:

- Protocol isolation – Modbus stays inside the field LAN; nothing routes outward.

- Data validation – checks for malformed registers, abnormal values, or timestamp gaps.

- Buffering – stores telemetry during outages to prevent missing data.

- Encryption – wraps all outbound data in TLS before transmission.

- Identity management – uses certificates to authenticate itself to the cloud.

This step turns raw inverter signals into trusted, structured telemetry.

3. Gateway → cloud via MQTT/TLS. Only encrypted outbound connections are allowed. The gateway publishes telemetry using MQTT/TLS 1.2/1.3, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and replay protection. No inbound ports are open, and the gateway communicates only with approved endpoints defined in its configuration.

4. Cloud / local SCADA / CMMS. Once in the cloud or local control system, the data is stored, analyzed, and used for dashboards, alarms, reporting, and maintenance workflows. Because the gateway enforces strict validation and encryption at the edge, the upper layers can rely on consistent, clean telemetry without compensating for device-level weaknesses.

For EPCs and asset managers, a consistent gateway layer simplifies operations across diverse sites. It enables vendor-agnostic onboarding, even when inverters vary by brand or generation. Security policies can be applied uniformly across the entire fleet, reducing the likelihood of misconfigurations. This approach decreases downtime, improves incident response times (MTTR), and strengthens overall system resilience, especially in distributed portfolios managed remotely.

You may be interested in: How PV inverters collect, log, and share solar performance data

How KaaIoT Universal Energy Controller implements cybersecurity best practices

The KaaIoT Universal Energy Controller applies security controls directly at the edge. It uses secure boot and signed firmware to prevent unauthorized modifications, and each device is identified by unique cryptographic credentials. All outbound traffic is encrypted via MQTT/TLS or HTTPS, and no inbound ports are exposed. The logger also performs edge buffering, timestamp validation, and gap detection to ensure data integrity during network interruptions. Hardware is FEOC-compliant and manufactured in Texas, supporting strict supply-chain requirements. For enterprises, this provides a unified and secure telemetry layer across Solis, Growatt, SMA, Fronius, SunSynk, Victron, and other inverter fleets. The device supports utility and IRA requirements for data provenance and sovereignty while reducing the security burden on EPC and O&M teams.

Checklist: how to validate that your solar logger is actually secure

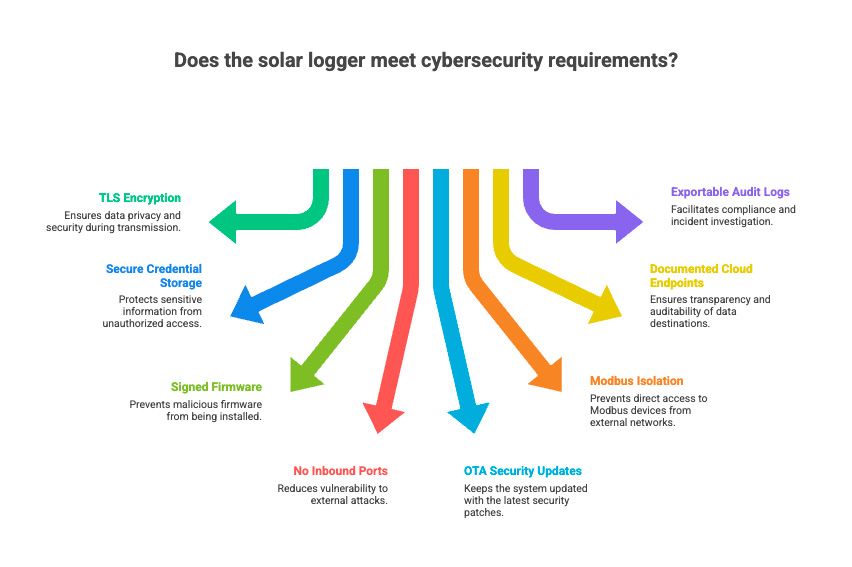

Use this checklist to quickly assess whether a solar data logger meets modern cybersecurity requirements. A device that fails any of these points introduces operational and regulatory risk.

- TLS encryption end-to-end for MQTT/HTTPS;

- Secure credential storage for keys, Wi-Fi passwords, and tokens;

- Signed firmware only, with secure boot enabled;

- No inbound ports exposed to the internet or local network;

- OTA security updates are supported and regularly maintained;

- Modbus is isolated behind a gateway, never routed directly outside the field LAN;

- Documented cloud endpoints, with transparent and auditable destinations;

- Exportable audit logs for compliance, incident investigation, and reporting.

Conclusion

The security of energy systems’ data channels becomes inseparable from the security of the infrastructure itself. Solar data loggers now sit at the core of monitoring, billing, and compliance workflows, and weak protection at this layer directly impacts operational reliability and financial accuracy. For EPCs, asset managers, and investors, a secure telemetry path is fundamental to trust. Strengthening this layer is not an added feature; it is a long-term safeguard for system stability, data integrity, and transparent performance reporting. Organizations that prioritize secure loggers and edge gateways build PV portfolios that can scale confidently and withstand modern cyber risks.

KaaIoT supports this approach with a secure, open, and verifiable architecture for energy monitoring, helping teams deploy protected telemetry across diverse inverter fleets without increasing operational overhead.